Your dog years can be better spent if you pay attention to your best friend

by David Dudley, AARP The Magazine

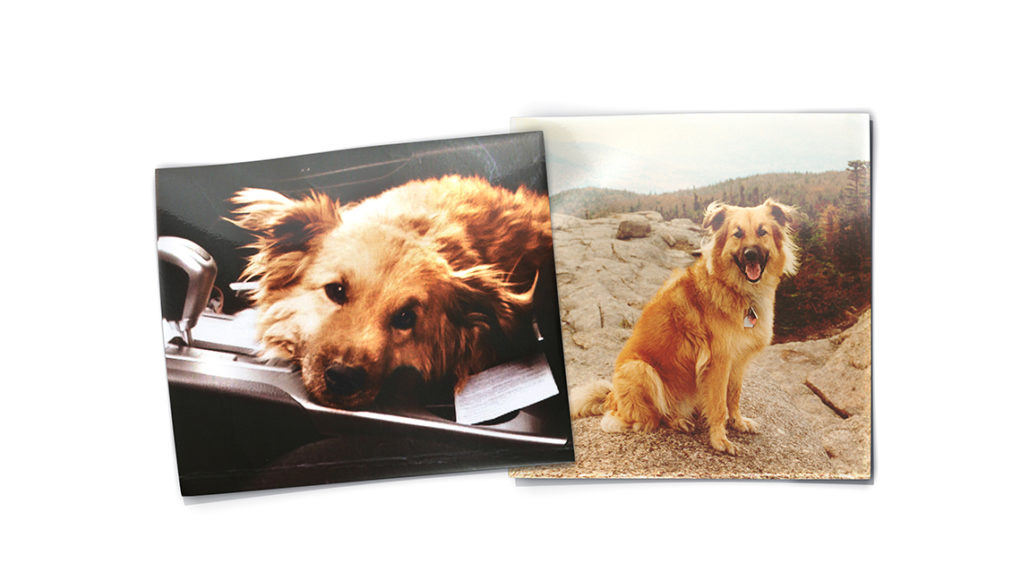

Foghat, the author’s dog, in 1995 at age 1, left, and in 2012 at age 18. — Courtesy of David Dudley; Photo illustration by Chris O’Riley

The dog is old.

Age snuck up on him. Maybe this will happen to me, too, if I’m lucky. Maybe it already has. But what human has the genes and the luck and the sheer savoir faire to disguise the years as well as this amazing specimen of canine charisma does?

His teeth are bright. His muzzle, black; his coat, feathery. He can bounce a soccer ball off his nose. On the street, everyone loves him. “Your dog is so pretty! How old is he?” they often ask. They’re astonished to hear the number. He’s 10. He’s 12. He’s 14. On it goes, year upon year. He’s ageless; he’s immortal.

But look closer. When he runs, his gait is stiff. In the depths of his irises, clouds are gathering — cataracts, says an eye doctor pal. “He’s old,” I tell everyone who asks. “He’s an old man.” I pat his head. “Aren’t you? Who’s an old man?”

The dog gazes up. Me?

“Dog years” are fluid things; smaller breeds live longer than big ones, and none seem to really get older and wiser, like we are supposed to do. Emotionally, a domestic dog exists in a kind of perpetual adolescence, a long summer twilight of play and napping and happy routine in the company of parents who never get old, and never let you grow up.

The scientific term for this Peter Pan state is “neoteny” — when adults retain juvenile traits — and it’s one of many characteristics of older canines to invite inquiry from longevity researchers. Daniel Promislow, who studies aging at the University of Washington, recently assembled scientists from various disciplines to join a Canine Longevity Consortium. Armed with a grant from the National Institute on Aging, they’re laying the groundwork for the first national longitudinal study on aging in dogs.

Why? The researchers are exploring an audacious idea: Dogs are in many ways our mirror species. “Unlike most [animal] models used to study aging, dogs aren’t in a lab — they share the same environment we do,” Promislow says. Domestic dogs exhibit huge genetic variability, eat processed food, sleep in our homes (hell, right on our beds) and enjoy access to humanlike health care.

Increasingly, they also get sick and die like us: They acquire arthritis and heart disease and many of the same cancers; they grow frail and forgetful. Often their lives are extended by expensive medical interventions. What Promislow and his colleagues hope to do is discover what factors allow some dogs to better fend off these indignities. One proposal: giving older dogs low doses of a drug called rapamycin, which has been effective in extending the lives of mice by up to 13 percent. The hope is that what works for them will work for us.

Sleep better and weigh less

We don’t know exactly how old the dog is. Rescued by a friend in the mid-1990s, this dog arrived a stray, skinny and wary but full grown. He was what sociologists would now call an emerging adult. This worked out, since I was one, too.

I acquired a dog as a statement of incipient maturity, right on the heels of the first decent apartment and a few years before marriage. This was an era of much questionable decision-making, and in that spirit the poor animal got a jokey name: Foghat, after the hirsute 1970s rock band. I just thought it sounded funny.

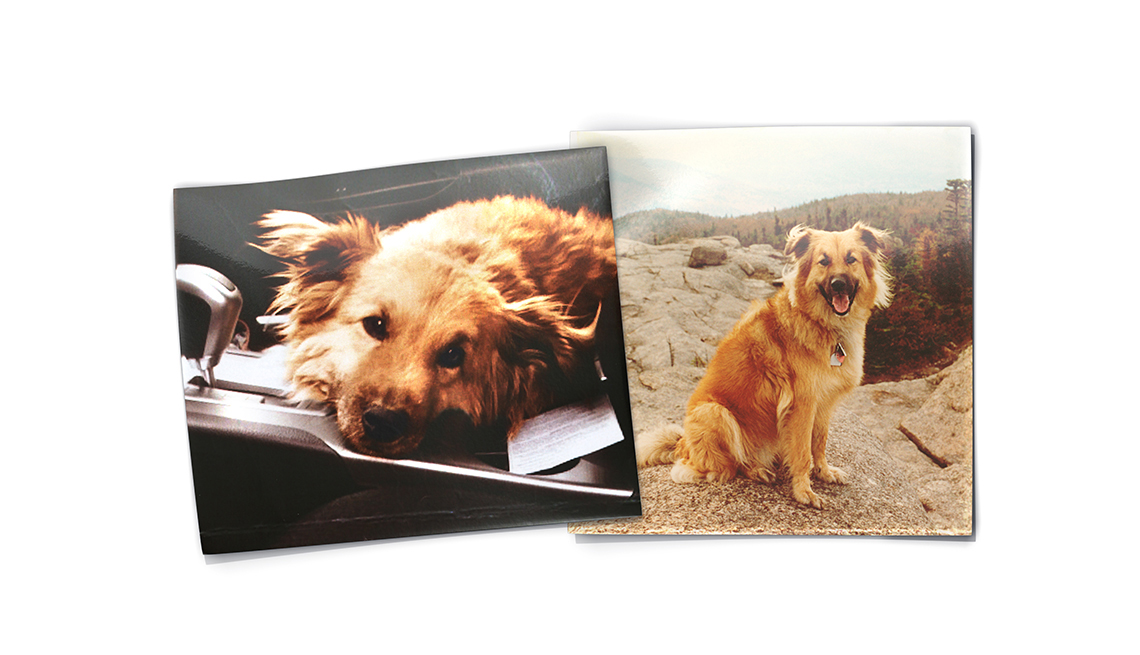

Christmas morning 1997, right, and wedding day, 1999. — Courtesy of David Dudley; Photo illustration by Chris O’Riley

Rival camps of behavioral scientists are still debating why our species is compelled to set up housekeeping with these carnivores. One theory: Humans and canids fell in with each other tens of thousands of years ago, beginning a process of mutual domestication that conferred survival advantages to both parties.

The more sociable wolves got leftovers and outcompeted their less-friendly kin; the early humans who tolerated such creatures discovered they were good hunting buddies and alarm systems, and thus the humans prospered. We are all descended from dog lovers.

And this evolution is ongoing, a process scientists call convergence: Human and canine genes, shaped by the environment we share, are evolving in lockstep. Today, along with home security and leftover disposal, dogs confer a host of wellness benefits, especially to kids and older people. People with dogs sleep better, weigh less and get more exercise than dog-free peers. And there are the less tangible perks, the ones cataloged in Marley & Me–style books. This burgeoning “dogoir” literary genre revolves around the reductive but basically correct idea that a dog is foremost an instrument of personal growth: It exists to ease your existential anxieties, impart lessons about love and friendship, and teach you how to be a better person.

Moving day, 2000, left, and a snowy winter of 2002. — Courtesy of David Dudley; Photo illustration by Chris O’Riley

At this, Foghat excelled. His initial role, as with many of his species, was to be a kind of ur-baby, a more rugged prototype of the real thing. His needs — food, walks, the occasional pill and swab of flea goo and dose of doggy Prozac (really!) in case of a thunderstorm — were modest but unremitting, and this litany of feeding and walks and belly rubs gradually carved a Foghat-shaped groove into my being.

In time that space grew to accommodate a new creature, with a more demanding routine. Foggy had settled into the languor of midlife when our first daughter was born, and his equanimity amid this disturbance was a great comfort. In a photo of me taken moments after returning home from the hospital, I’m sitting on the couch wearing a dazed look of muted new-dad terror and holding a tiny infant in one arm; the other arm rests atop the dog’s proffered belly. He’s sprawling luxuriously beside me on the couch, eyes half closed, projecting “Everything will be OK” vibes. This, he seemed to understand, was to be his job from now on.

Doggy dementia

Neuroscientist Elizabeth Head, who studies senior citizen beagles at the University of Kentucky, understands the minds of aging dogs. By middle age, dogs become resistant to change. They take longer to learn new things and start lagging in memory tests. At age 6 or 7, even healthy beagles in Head’s studies show signs of the microscopic beta-amyloid plaques that are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease; about a third of them will ultimately succumb to canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome, aka “doggy dementia.” That’s a close parallel to the percentage of Americans 85 or older who will get Alzheimer’s.

And the dogs’ plaques look a lot like those in humans — more so than the ones found in our fellow primates. Head is not sure why. “It could be that living in our environment — our food, our water, our homes — has made dogs more vulnerable,” she says. Age-related dementia, in other words, might be “a feature of the domestication process,” she says, a kind of unintended side effect of civilization.

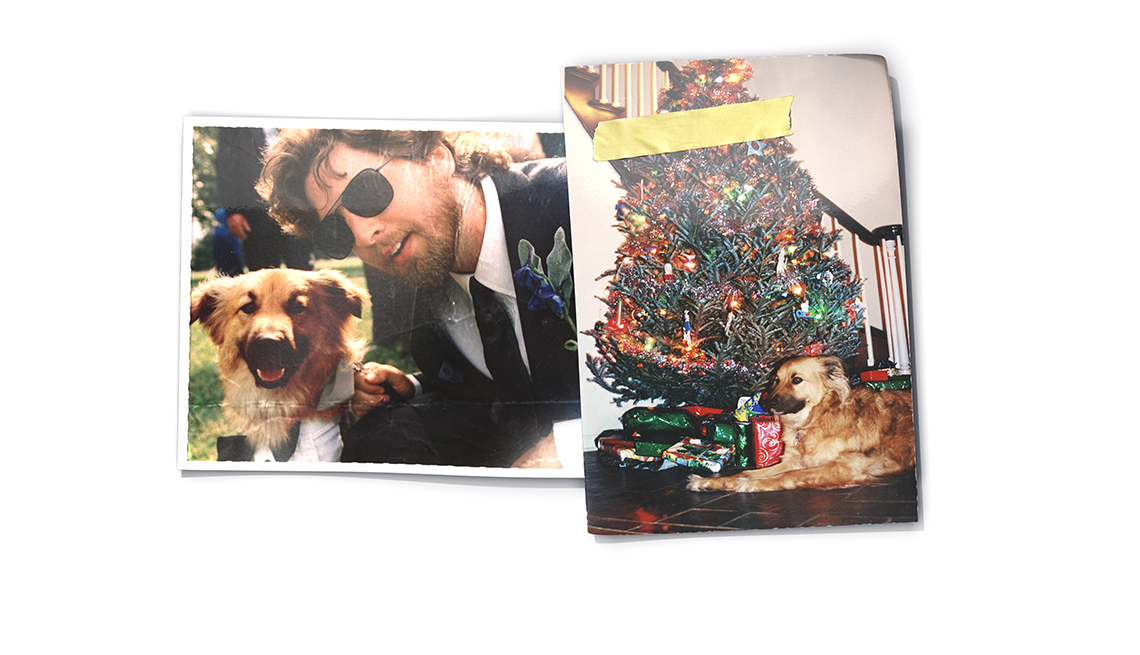

The baby arrives: Foghat with our daughter Nora in 2005, left, and again in 2006. — Courtesy of David Dudley; Photo illustration by Chris O’Riley

And Head thinks dogs can help defeat it. In past studies, she demonstrated that an antioxidant-rich diet and “behavioral enrichment” — a course of memory drills and new-skills training — can significantly delay or diminish plaque development and memory impairments. In a coming study, Head wants to refine this regimen and try to stop brain decline entirely in middle-aged animals, before they pass that cognitive point of no return.

Whatever age-proofing formula Foghat stumbled upon — maybe it was his expensive premium dog food, the behavioral enrichment he received from evading toddlers, or the lifelong regimen of heavy napping — he entered his dotage in roaring good health. Around his 18th birthday, I Googled “oldest dog in the world,” because I started to wonder if he was closing in on a record. He was what gerontologists would call a successful ager.

And then, seemingly overnight, he wasn’t. If you have to go — and you do — a swift slide into decrepitude is the preferred way. The phrase is “compression of morbidity,” when the infirmities of age are delayed until the bitter end. Still, it’s no picnic. The joints went first. He started limping after a vigorous bouncing-a-soccer-ball-off-his-nose session. Then he needed help climbing into the car or crawling under the bed, his favorite sleeping spot. Our epic rambles through the woods became short hikes, then brief spins around the block. Sometimes he’d stop midwalk, frozen like a Parkinson’s sufferer. The stairs grew perilous. He became a wandering insomniac, barking at ghosts, claws clacking aimlessly through the darkened house. He’d vanished into the shadowlands of canine cognitive dysfunction, and he would not be coming out.

This was inconvenient. It strained our household’s delicate structural integrity. We were in sandwich generation mode, working spouses with small kids, an aging parent down the road, and a complement of adult-grade responsibilities. The geriatric dog added an extra layer of filling to life’s overstuffed Dagwood. Each morning, when I came downstairs, I stopped to inspect the prone body on the landing, wondering, with a mix of hope and dread, if he’d passed quietly in his sleep, the way we all say we want to do. Eighteen years! Longer than childhood, longer than marriage (so far). Seeing this ancient animal was like stumbling upon a living fossil, an artifact of a vanished age.

At the same time, it was also a glimpse into the future. Foghat’s senescence appeared as both a comfort and a warning of what awaits: Some fears and eccentricities will lift with the years; others will only deepen. One by one, the things you love to do become too difficult and slip out of your life. But despite it all, you will still be you, and people will still cherish your wobbly presence. Even a diminished life is worth living on its own terms.

Until … when? Sometimes in those last months I’d rest my forehead on his brow and look searchingly into his great brown eyes, trying to divine his advance-care plan across the species barrier. I’d stare; he’d stare back. Are you still in there? Are you ready to go?

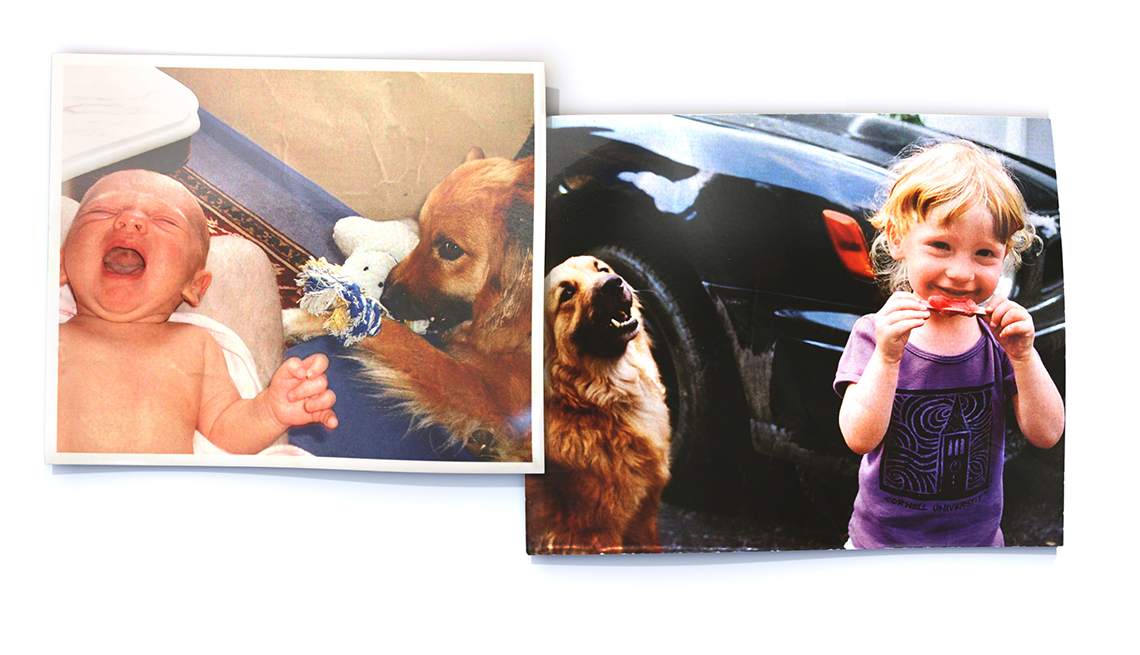

Another new home, 2007, left, and another new arrival, 2009. — Courtesy of David Dudley; Photo illustration by Chris O’Riley

Like losing a child

Getting a puppy, the comic Louis C.K. observed, is a “countdown to sorrow.” Inscribed in the act of welcoming this adorable fur ball into your home is the moment of its death a decade or so hence. Grief over a pet can equal or exceed that of a human family member, studies show. This is canine neoteny’s cruel flip side: Yes, your dog gets to be an emotional adolescent into ripe old age. But when he dies, it will feel like losing a child.

Foggy’s 18-year countdown finally ended one winter morning. Despite my best efforts to give him the good death he deserved, it was just as terrible as I’d feared. My wife held him in the backseat as I drove to the vet. He’d always loved car rides, but this time he writhed weakly and whined, intuiting correctly that something bad was up. As I carried him in, he let out a single unearthly howl, a sound he’d never made before. Then he relaxed, went still and struggled no more.

Soon we were standing around a metal table, clutching the dog just as we once did when a thunderstorm passed, trying and failing to project “Everything will be OK” vibrations. When the drugs hit his heart, I blurted out, “Sorry, buddy,” and crumpled into unseemly bawling.

The gerontologist Kenneth Doka has called the death of a pet “disenfranchised grief.” It’s a loss whose significance others don’t recognize. You’re not supposed to sit shivah for your schnauzer. You post a sad Facebook update and go back to work, as I did. When I came home in the evening and opened the front door, I was struck by the strange new stillness — the foreign silence of a household without a dog. It was as if a machine that had been humming in the background for a long time had suddenly been switched off.

In this absence, I have enough life lessons for a thousand dogoirs. I learned that it’s impossible to determine precisely when another being’s life is too compromised to go on, and that a long and enviable health span can’t save a good dog from a bad death. Maybe even a good death is pretty bad. Life is worth it; its absence is unfathomable. Sorry, buddy.

And now that I’m no longer young, and he’s dead, I’ll do my best to follow the path Foghat blazed into my life’s last half. This is sound medical advice, as neuroscientist Head says: “Everything you do for a dog to help them age well, you should do with them.”

So eat the best food you can afford. Go for a walk, even if it’s raining. Take a lot of naps. Keep your teeth clean and your breath fresh, so that the people you lick will not flinch. And when someone you love walks in through the door, even if it happens five times a day, go totally insane with joy.